If you’ve kept up with my blog posts, first of all, thank you. Secondly, you might have noticed that my reviews and analyses for games this year are longer, more critical, and more academically informed. This is deliberate, of course. I’m more interested in writing about games through a cultural lens nowadays than evaluating it as a product for consumers. Before I started writing about games, I didn’t really read video game reviews. In fact, I kind of detested them, which is also why I don’t score games in my reviews. Simply reviewing a game based on the gameplay, its story, and the graphics / visual aesthetic, and treating those aspects like completely separate things is a pretty shallow way of talking about a work of art and entertainment. But before I crawl up my own asshole, let me also say that sometimes we like things for base reasons.

Sometimes we like a game because the gun shoots good or the airplane goes brrrr. A couple of weeks ago, I played the game Carrion and I came away really enjoying it for fairly simple reasons. So compared to my previous reviews, this review of Carrion is going to be shorter and more conversational, while also discussing the game in a holistic way rather than simply breaking it down along the lines of gameplay, graphics, and story.

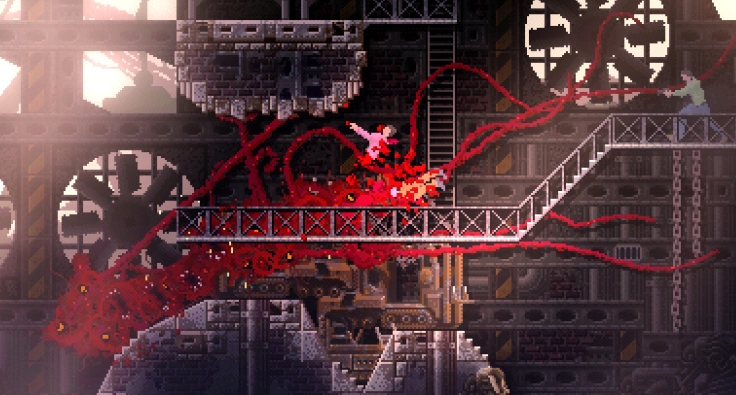

Marketed as a “reverse horror game”, in Carrion you play as an amorphous monster composed of teeth, tentacles, and viscera. Your goal is simple: escape the underground research facility you were imprisoned in and kill anyone that stands in your way. From the get-go, there is a raw feeling of power and momentum to the creature, a feeling that carries throughout the game’s breezy five-hour runtime. With its awesome monster design and fantastic atmosphere (created by the game’s superb sound design and soundtrack), Carrion is a fantastic and horrifying throwback to the sci-fi monster movies of the 70s and 80s.

Carrion can be loosely described as a 2D Metroidvania. As you rip and tear through the research facility, you acquire abilities that make previously inaccessible areas available. I say “loosely” because compared to other modern Metroidvanias, Carrion is a very linear and barebones game. The player is always guided on where to go and the game will intentionally guide you back to areas you previously visited if you need to return to them. There’s never a point in Carrion where you acquire a new ability that will open an area up and then purposely backtrack to that area. Reflecting this linear design is the fact the game has no map, which is unusual for a Metroidvania. Carrion honestly might be better off with a map than without it, but this design choice reinforces its premise: that you are a single-minded, unstoppable, horrifying force of nature.

The game’s opening momentum never fully ceases. Enemies are little more than speedbumps and rarely is Carrion a very challenging game. Dispatching an enemy is simple, but they are not completely defenseless and if a soldier catches you off-guard or pins you into a corner, they do pack a punch. But as you acquire more abilities, newer abilities are very effective at killing tougher opponents, nullifying them as obstacles. Your health is reflected in the monster’s size, so when a soldier does inflict a lot of damage, you shrink down to a tiny blob. You dramatically go from this badass, ravenous beast to this helpless-looking thing, and that makes you truly feel the monster’s power. Sometimes, though, you want to be small. Different abilities are tied to the monster’s size, and the game will require you to grow or shrink to access different abilities to solve a puzzle and progress through the area.

While I found these puzzles to be clever, they are also not very difficult, and just like the game’s enemies, they are only speedbumps on your rampage. Because of Carrion’s quick momentum, slower horror moments are not well signposted. But if you pause for a minute, you’ll begin to notice and recreate classic horror movie scenes you’ve seen in films like Alien or Predator. As guards patrol the hallway below an air duct, you can grab one guard and pull him through the vent, dispose of him, and then sneak up behind his buddy. Or if a scientist hears you and runs away screaming, you can follow him and slowly rip open the door to the room he is cowering in.

As a kind-of cross between The Thing and The Blob, controlling and moving the monster in Carrion feels exactly how I would want it to feel – chaotic. You are fast and deadly, but also clumsy and ungraceful. There’s a brilliant undercurrent of comedy in Carrion as you thrash around, destroying everything in your way. You are not a leopard on the African savannah, you are a 2-ton great white shark at SeaWorld that flopped out of its tank, gobbling up unassuming Ohioans. Tentacles will randomly shoot out and fix themselves to the walls and ceiling as you pilot the hulking mass of destruction through hallways, into air vents, and down elevator shafts. The right stick (or the mouse on PC) is used to rip off vent covers and pry doors off their hinges, but, more importantly, is also used to grab people, swing them around, and pull them into your gaping maw.

At first, I felt a little uneasy, horrified even, at my power. Do these defenseless people deserve to have their legs ripped from their torsos and swung around like a dog with a chew toy? Through several flashback sequences, it becomes abundantly clear these faceless scientists, soldiers, and bureaucrats messed with a force of nature they shouldn’t have messed with. As you progress further into the facility, you begin to hear cars and see skyscrapers on the horizon, revealing that these researchers kept this monster beneath a densely populated urban area, endangering the lives of innocents. I quickly came to realize that a) these people deserve what’s coming to them and b) it’s damn fun to be the monster.

In this regard, Carrion shares the themes of many classic monster movies. The monster is the result of government, military, or corporate organizations disregarding the wellbeing of society and the natural environment, usually in their desire for power (be it scientific, technological, or financial). We sympathize with the monster because its rage is not its fault. As an American in the year 2020, the raw, destructive power of Carrion’s monster is more than entertaining, it’s cathartic. I think this is why I enjoyed this game so much. Besides being a fan of the game’s influences and its overall vibe, what made Carrion so appealing to me is how its monster expresses the frustration and resentment we have towards those in power. But of course, this is simply my interpretation. As China Miéville states in his “Theses on Monsters”, “Monsters demand decoding, but to be worthy of their own monstrosity, they avoid final capitulation to that demand…Any bugbear that can be completely parsed was never a monster, but some rubber-mask-wearing Scooby-Doo villain, a semiotic banality in fatuous disguise. It is a solution without a problem” (2012).

Carrion is available on the Nintendo Switch, PC, PS4, & Xbox One.

What do you think of Carrion? Let me know in the comments below!

Like this article? Check out my own blog at https://jacobhamill.blog/ for more content.

References

Klepek, P. (2020, August 14). How ‘Carrion’ built empathy for its fleshly monster. Vice. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/4ay5x3/how-carrion-built-empathy-for-its-fleshy-monster

McDonald, J. (2019, October 31). Sometimes the served head rolls left. Jacobin. https://jacobinmag.com/2019/10/horror-movies-monsters-politics

Miéville, C. (2012). Theses on monsters. Conjunctions, 59. Retrieved August 31, 2020, from http://www.conjunctions.com/print/article/china-mieville-c59

Leave a comment