Warning! This article contains story spoilers for Hades.

“Ugh, witches,” the protagonist groans. Weaving around a barrage of projectiles in a room filled with deadly magma, I am inevitably caught by one stray projectile too many. “There Is No Escape.” This all-too-familiar message flashes across the screen as I watch the hero fade into a pool of blood, ready to be whisked away to the lavish House of Hades. A few seconds later, he emerges, now back at the game’s beginning. “Again,” he says.

Hades is a Greek mythology-themed roguelike video game developed and published by Supergiant Games. You play as Zagreus, the son of Hades, who wishes to leave the Underworld (and with it his father’s belittling attitude) and join his distant relatives on Mount Olympus. The Underworld, however, is meant to keep souls in, so Zagreus must fight, chamber by chamber, through his father’s realm, to reach the land of the living.

As a roguelike, Hades is structured around dying and restarting. Death is not a novel experience in video games, but roguelikes, notorious for their difficulty, center this experience in their game design. You are expected to die repeatedly, but unlike many of its roguelike cohorts, Hades centers this experience narratively as well. Narrative progress is not tied to winning and the game’s story largely unfolded across my thirty-two failed runs before I finally achieved victory.

But to my surprise, Hades’ narrative does not end once you set foot beyond the Underworld because, as the game told me thirty-two times already, “there is no escape“. We learn eventually that Zagreus’ quest to join the Olympians is a ruse; he is actually searching for his long-lost mother, Persephone. And it is when Zagreus finally escapes the Underworld, gazes upon the rising sun for the first time in his life, and meets his mother in person, we learn the cruelest meaning behind “there is no escape”. Zagreus is bound to the Underworld and can only exist in the land of the living for a brief amount of time until he dies and is returned, once again, to the game’s beginning. For our hero, escape is fleeting.

It is Zagreus’ fate to continuously fight through the Underworld only to taste momentary success. Hades’ interpretation of Greek myth is more than surface aesthetic — the game uses its roguelike structure to convey the themes of the mythology it draws on. Zagreus’ struggle against this predetermined fate connects him to the conflicts of many characters in Greek myth and tragedy, and, through the endless cycle of dying and restarting, Hades asks us to consider the power fate holds in our lives and how much control we have over it.

Hades has been a massive success for Supergiant Games, selling over one million copies just days after leaving early access (Gurwin, 2020). The game’s mass popularity is surprising considering it belongs to a genre known for its punishing difficulty and esoteric nature: the roguelike. Games like Binding of Isaac, Spelunky, and Dead Cells require their players to devote many hours to accumulating skill and knowledge over an untold number of failed runs. But for Hades’ creative director, Greg Kasavin, the “hardcore” reputation of roguelikes is not what attracted his team to the genre. In an interview with GameSpot, Kasavin says, “Roguelikes are categorized by their punishing difficulty. It’s a source of pride….We don’t think that’s integral, though; the thrill comes from the idea that the game can surprise you over and over again” (Garst, 2020).

If the genre is characterized by its difficulty, then it is equally characterized by its randomness. Roguelikes emphasize dying and restarting and, through procedurally generated content, the idea is that no two runs are exactly the same. Kasavin and his team were inspired by the variety in mechanics a player could experience from run to run in Slay the Spire, a deck-building card-battler roguelike. “On one hand, you might push towards a certain build, but the randomness is going to fight against you. That decision-making part of roguelikes is super interesting,” says Kasavin. “Difficulty has nothing to do with any of that” (Garst, 2020). And there is historical evidence to back up Kasavin’s assertion.

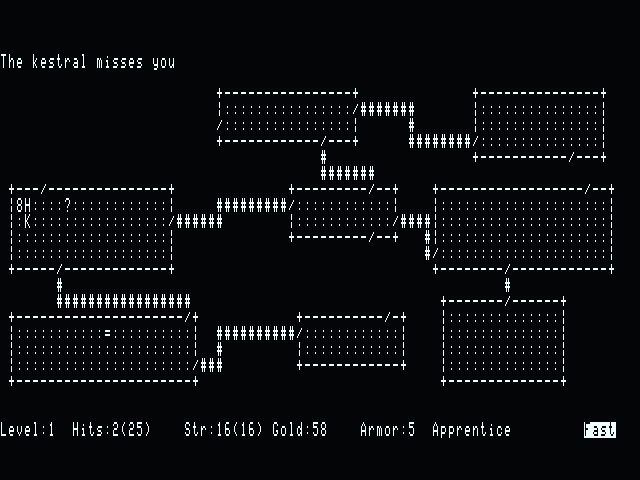

The term “roguelike” literally means “games like Rogue”. Rogue was developed in 1980 by UC Santa Cruz students Glenn Wichman and Michael Toy. In Rogue, the player explores a dungeon in search of a magical amulet, fighting off monsters, and collecting treasure. Rogue was character-based (as opposed to text-based adventure games like Colossal Cave Adventure) and featured procedurally generated dungeons and permadeath. By the early 1990s, there were a number of games inspired by Rogue, games like Moria, Angband, and Hack (later NetHack), and, like their progenitor, these games were character-based and open-source (Moss, 2020).

A niche community of devs and players grew around these games, so much so that in 1993 a Usenet user proposed creating a new hierarchy to group these games together for ease of discussion (Zapata, 2017). In July 1993, the newly appointed group moderator for ” rec.games.roguelike.misc” created an FAQ to help define what makes a game a roguelike. The FAQ states,

“Although the common features of Rogue and its many descendants are ‘obvious’ to many people, they are difficult to describe in simple terms. All of the games mentioned below are single-user, fantasy role-playing computer games, generally set in a dungeon, run with a simple graphics interface… Logistically, they’re all free games, executables, and generally sources, are available by FTP” (Zapata, 2017).

This early definition of roguelike does not include many of the design features we would consider inherent to the genre today. There is no mention of permadeath, proc-gen content, or punishing difficulty. In fact, when asked about permadeath in modern roguelikes at 2016’s Roguelike Celebration, Rogue co-creator Glenn Wichman said, “permadeath wasn’t implemented in Rogue as the ultimate trial of player skill…It wasn’t meant to be a signifier of permanent, painful failure…More important to the roguelike genre is simply the inability to undo decisions that lead to death” (Francis, 2016).

While roguelike elements steadily leaked into mainstream commercial games during the 1990s and 2000s, the genre itself remained incredibly niche until the late 2000s and early 2010s (Moss, 2020) when it crossed over into the mainstream with the rising popularity of downloadable indie games. It is around this time you begin to see a differentiation between “roguelikes” and “roguelites”. Roguelite games are perceived as less punishing and more approachable than their roguelike forebearers because they in some way alleviate the sting of permadeath (Klepek, 2020). By this definition, Hades would be considered a roguelite, but its approach to death shares the same design philosophy of Glenn Wichman — that death is not a “signifier of permanent, painful failure” and more of an example of “consequence persistence” (Francis, 2016). Hades is not a departure from roguelike design choices, it is true to the spirit of the genre. Its innovation is in how the player’s experience of death is shared narratively by the protagonist.

Death is progress in Hades. Conversations open up, new characters appear, and even major plot points are revealed across failed runs. In an interview with VICE, Greg Kasavin said, “From the start…we put special focus on the moment of death in Hades, knowing it would be something players would see frequently” (Klepek, 2020). He goes on to say, “So we figured, this needed to be core to the narrative. If the player doesn’t forget their deaths and learns from them, so should the protagonist.” Death is not simply a mechanical tool used to make the player consider the lasting consequences of their decisions, death is a narrative tool, experienced and remarked upon by Zagreus. The whole game, mechanically and narratively, revolves around dying and restarting.

After their last game, 2017’s Pyre, Supergiant wanted to make a game with a branching story that was also highly replayable — the Greek mythology theme came shortly after (Wiltshire, 2020). While reading the works of Homer, Ovid, and Hesiod, Greg Kasavin came across the god Zagreus. There are few details about Zagreus, one being that he might have been the son of Hades, but this lack of information made him an interesting blank slate, allowing the team to invent their own story (Wiltshire, 2020). Setting the game in the Underworld, the realm of the dead notorious for its inescapability, seemed natural and aligned with the experience of repeated death. “The repeating roguelike structure slotted neatly into the idea of him running away after a fight with dad, failing, and finding home again”, says Kasavin (Wiltshire, 2020).

But Kasavin and his team borrowed more than just characters and setting from Greek myth. I think it is no coincidence that the Greek mythology theme fits so well into the existing roguelike formula. Hades’ connection to Greek myth is far deeper than surface-level aesthetic, it is thematically tied to the very mythology it is inspired by.

The purpose of mythology is complicated. People naturally want to understand the world around them and their connection to the world. Yet, there are many things beyond our comprehension and control so people create stories to explain that which is unexplainable. But a myth’s purpose is not just to provide an answer. Myths are narratives. They give us the sense that there is a reason for everything; that there is causation to the past (Martin, 2016, pp. 39-41). From an anthropological view, myths can be described as stories that help explain a culture’s worldview, their interpretation or perception of reality (Stein & Stein, 2016, pp. 29-32). Today, with the advancement of science, we no longer rely on myths to help us understand why the seasons change or why earthquakes happen, but there are still things that remain beyond our understanding, and, in all likelihood, forever will.

Death is an inevitable experience, yet what happens when and after we die remains a mystery. The ancient Greeks believed that something left the body upon death. That something, whose presence and power was taken for granted by the living, was called the psyche, meaning breath (Burkert, 1991, p. 195). The psyche was thought of as a reflection, an image that could be seen but not touched, and the final destination for one’s psyche was a realm beneath the earth — perhaps coming from the Greek’s practice of burying their dead in simple pits lined with stones, or in the case of cremation, burying an urn (Burkert, 1991, p. 191).

This realm was overseen by the Chthonic gods, viewed in opposition to the gods of the heavens, the Olympians. The Olympians hate and fear the Underworld, but despite this opposition, the two form a polarity in which one cannot exist without the other. Together they constitute the universe and from which they derive their fullest meaning (Burkert, 1991, p. 202). Heaven is contrasted with earth, day with night, celebration with lamentation, and immortality with mortality.

Life and death defines us as mortals and distinguishes man from the gods. And while man can pray to the gods, offer them gifts, and earn their favor, the gods cannot save man from death. Apollo does not save Hector from his demise, nor does Artemis save Hippolytus (Burkert, 1991, pp. 201-202). The Olympians respect the sanctity of death and while the Chthonic gods oversee the dead in the afterlife, they themselves do not control death. That power is left to the Fates, the three sisters Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos. Born from Nyx and Erebus, they themselves descended from primordial Chaos, the three Fates control the thread of life for every mortal. And while some stories claim the gods can occasionally intervene on a mortal’s behalf, others say that even Zeus cannot control the power of the Fates and is subject to them himself (Graves, 1957, p. 48).

Regardless, there are many examples in Greek mythology of mortals failing to circumvent the absoluteness of death. The musician Orpheus descended to the Underworld in an attempt to bring back his beloved Eurydice and although Hades grants Orpheus his wish, Orpheus inevitably looks behind him, despite being told not to, losing Eurydice forever (Graves, 1957, pp. 111-115). The mischievous Sisyphus evades death twice, once by holding Hades prisoner in his house and the other by lying to Persephone, but is ultimately forced to return to the Underworld by Hermes and is punished with the task of rolling a boulder up a hill for all eternity (Graves, 1957, pp. 216-218). Death is not only inescapable, it is an experience beyond the control of the Olympians, wielded by deities closely related to Chaos, an unfeeling, uncaring expanse predating the universe.

When we talk about Greek mythology, we’re talking about a range of traditions and beliefs that stemmed from rituals and oral traditions, that were eventually written down, and have been reinterpreted, rationalized, and allegorized for centuries. Ancient Greek religion had no set dogma, sacred text, or religious class, so poets and thinkers could build on older stories, change them, reinterpret them, all without needing their audience to accept these new interpretations as fact (Martin, 2016, pp. 15-16). According to Lorna Hardwick, a professor of classical studies and an expert on classical reception, “Myth acts as a conduit, moving across and between the borders of fiction, imagination, religious practices and social norms…Refigurations of myth signaled shifts and conflicts in ways of looking at the world” (Hardwick, 2017). Greek and later Roman writers were reacting to and inserting new ideas into familiar myths in the same way we today refigure the writings of Sophocles, Euripides, and Ovid.

The Greek tragedy is a form of drama that emerged during the 6th century BCE in the open-air theaters of Athens. Writing in the 4th century BCE, Aristotle defined the tragedy in his Poetics as a work that seeks to elicit pity and fear in the audience to evoke a cathartic reaction (Aristotle, 2014 [ca. 335 BCE], p. 23). This catharsis, later redefined by Aristotle as ‘wonder’, is not simply meant to make us feel ugly emotions, it is to display the limits of what is human. “Tragedy is about central and indispensable human attributes, disclosed to us by the pity that draws us towards them and the fear that makes us recoil from what threatens them” (Sachs, n.d.).

The ancient myths the tragedies were based on presupposed that man, struggling in vain, was at the mercy of heavenly powers or divine fate. But the tragedy’s fixation on human nature asks us to consider what freedoms man has in the course of his fate (Agard, 1933, p. 121). More often than not, the characters in Greek tragedies fall to their predetermined fates not because of divine intervention or power, but because of their own choices — or what Rogue’s co-creator might describe as “consequence persistence”.

The tragedians took the ancient myths and explored the consequences of human choice, the failures and achievements of human freedom (Agard, 1933, p. 126). Oedipus’ actions to avoid his destiny leads him to famously kill his father and marry his mother. In Antigone, Creon’s belief that what he is doing is best as a ruler leads to the death of his son and the instability of Thebes. And though not a tragedy, Achilles’ refusal to fight in the Iliad results in the death of Patroclus, filling Achilles with rage and leading him towards his prophesied death. Greek tragedy forms the bedrock of Western literature and their exploration of death, fate, and free will has influenced and captivated writers and scholars for centuries. When new media reimagines classical mythology, there is a co-authorship occurring between ancient writers, modern authors, and the audience, resulting in new ways of looking at the world grounded in a familiar mythological past (Hardwick, 2017).

So how does Hades fit into the long history of refiguring Greek mythology? The theme of fate and the extent of free will is the connective thread here. If roguelikes are designed around the experience of dying and restarting, then permadeath is a mechanic to make players consider the decisions taken in a run that led to their death, or “consequence persistence”. Procedurally generated content ensures that no two runs are exactly alike, making the weight of our decisions ever more impactful. We, the player, ultimately cannot control what happens from run to run, what powers we may receive, or what enemies we face. But we can choose which path to take, what upgrades to accept or decline, where to spend our earned money, and these decisions can lead the player to have either a successful or unsuccessful run.

Zagreus’ stubbornness motivates him to repeatedly fight his way through the Underworld and is what eventually leads him to discover that he can never really escape his father’s realm. Despite knowing this, he continues to fight and struggle against his fate. We come to learn that Lord Hades was prophesied to never have an heir. Zagreus was born stillborn and the goddess Nyx used her power to give Zagreus life, but it was too late, Persephone had already left the Underworld in grief. Zagreus’ death is what drives his mother away, yet that which gives him life, the Underworld, keeps him from reuniting with her. “Born of Chaos, the Underworld is a domain of pure and utter darkness…That darkness…connects the bearer to the Underworld, makes them inseparable. Almost one and the same. Those born of darkness must remain in darkness” (Hades, 2020).

This divine fate is inescapable, a law of the Underworld, but instead of accepting this fate at face value, Zagreus, in all his stubborn defiance, exerts a significant amount of free will within the confines of his fate to shape a desirable outcome. This a freedom the Greek tragedians believed man has. “We are not free to escape our destiny; but we are at least free, knowing the consequences, to decline the possibility of avoiding them by compromise. We can choose to save our own integrity” (Agard, 1933, p. 124). That is exactly what Zagreus does. He does not escape the Underworld but he is able to repair his family by convincing Persephone to return to the House of Hades. By doing so, he earns his father’s respect, a step towards mending their relationship, and is given official approval to continue breaking out of the Underworld to stress test the realm’s security.

Zagreus must continue trying to escape the Underworld because then, quite literally, there would be no more game to play. But Zagreus’ continued struggle is also the same struggle we face in our daily lives. Just like Zagreus’ innate connection to the Underworld or what a player encounters from run to run, there are things in our lives we have no control over — a pandemic, an election, what material conditions we are born into — but we can at least embrace these circumstances and are free to exert our will within the choices made available to us.

Zagreus’ fate to forever fight his way through the Underworld, despite knowing his victory is only momentary, is similar to the fate of Sisyphus, tasked with eternally pushing a boulder up a hill, only to have the boulder topple down the side when it reaches the top. In his famous essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, French philosopher Albert Camus explains that human existence is defined by the Absurd. Man desires order, meaning, and purpose in life in spite of the chaos and indifference of the universe (Camus, 1991 [1942]). To Camus, Sisyphus is the absurd hero, accepting and embracing this absurdity. Sisyphus embraces his punishment, despite knowing the boulder will always roll away, and finds meaning and satisfaction in his daily struggle. We should aspire to be like Sisyphus. Camus concludes his essay with, “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy” — with Zagreus, we don’t have to imagine.

…

Thanks for reading!

Hades is available for the PC and Nintendo Switch

Check out my own blog, jacobhamill.blog, for more content.

References

Agard, W. R. (1933, November). Fate and Freedom in Greek Tragedy. The Classical Journal, 29(2), 117-126. JSTOR. Retrieved November 3, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3290417?seq=8#metadata_info_tab_contents

Aristotle. (1907). The Poetics of Aristotle (S. H. Butcher, Trans.). University of California, Berkeley. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Poetics_of_Aristotle/OdBDAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0 (Original work published ca. 335 BCE)

Burkert, W. (1991). The Dead, Heroes, and Chthonic Gods. In Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical (pp. 190-215). John Wiley & Sons.

Camus, A. (1991). The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays (J. O’Brien, Trans.). Vintage Books. https://www2.hawaii.edu/~freeman/courses/phil360/16.%20Myth%20of%20Sisyphus.pdf (Original work published in 1942).

Francis, B. (2016, September 19). Rogue co-creator: permadeath was never supposed to be ‘about pain’. Gamasutra. Retrieved October 28, 2020, from https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/281688/Rogue_cocreator_permadeath_was_never_supposed_to_be_about_pain.php

Garst, A. (2020, October 17). Hades Changes What It Means To Be A Roguelike. GameSpot. Retrieved October 26, 2020, from https://www.gamespot.com/articles/hades-changes-what-it-means-to-be-a-roguelike/1100-6483420/

Graves, R. (1957). The Greek myths. G. Braziller. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006809240

Gurwin, G. (2020, September 20). Hades Has Sold 1 Million Copies, Nearly One-Third Sold In Last Few Days. GameSpot. Retrieved October 24, 2020, from https://www.gamespot.com/articles/hades-has-sold-1-million-copies-nearly-one-third-sold-in-last-few-days/1100-6482388/

Hades (Switch version) [Video game]. (2020). San Francisco, CA: Supergiant Games.

Hardwick, L. (2017). Myth, Creativity and Repressions in Modern Literature: Refigurations from Ancient Greek Myth. Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics, 40(2). Gale Literature Resource Center. Retrieved November 1, 2020, from https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A597253065/LitRC?u=colu68650&sid=LitRC&xid=528b6874

Klepek, P. (2020, October 5). How ‘Hades’ Made a Genre Known For Being Impossibly Hard Accessible. Vice. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.vice.com/en/article/889zqa/how-hades-made-a-genre-known-for-being-impossibly-hard-accessible

Martin, R. (2016). Classical Mythology: The Basics. Taylor and Francis. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

Moss, R. C. (2020, March 19). ASCII art + permadeath: The history of roguelike games. Ars Technica. Retrieved October 28, 2020, from https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2020/03/ascii-art-permadeath-the-history-of-roguelike-games/

Sachs, J. (n.d.). Aristotle: Poetics. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://iep.utm.edu/aris-poe/#H5

Simpson, D. (n.d.). Albert Camus (1913-1960). Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved November 4, 2020, from https://iep.utm.edu/camus/#SSH5ci

Stein, R. L., & Stein, P. L. (2016). The Anthropology of Religion, Magic, and Witchcraft (Third ed.). Routledge.

Wiltshire, A. (2020, February 12). How Hades plays with Greek myths. Rock Paper Shotgun. Retrieved October 25, 2020, from https://www.rockpapershotgun.com/2020/02/12/how-hades-plays-with-greek-myths/

Zapata, S. (2017, November 13). On the Historical Origin of the “Roguelike” Term. Slashie’s Journal [Blog]. Retrieved October 28, 2020, from https://blog.slashie.net/on-the-historical-origin-of-the-roguelike-term/

Leave a comment