CW: This article discusses homophobia, transphobia, sexual assault, ableism, and mental health. It also contains spoilers for Persona 3, Persona 4, Persona 5, and Catherine.

It’s never a great feeling when you revisit a piece of media you love only to realize it’s not as good as you remembered it. It’s an even worse feeling when you realize the thing in question is deeply problematic (and yes, “problematic” is a very vague and unhelpful term but just bear with me). For me, that realization has clarified over the past year or so with the Persona series, a JRPG series created by Atlus that I have enthusiastically spoken about and recommended on many occasions. A year or two ago, I probably would have said that Persona 4 is one of my favorite games of all time, and it might still well be. This article is not meant as a pity party, instead, it’s a critical dissection of Atlus’s checkered history when it comes to the representation of marginalized folks. What I’m writing here is nothing new, plenty of people from all backgrounds have called Atlus out on this issue before. Nor do I, a straight guy, consider my voice to be an authority on this subject, but I do feel like I owe it to myself, and maybe others, to write about the Persona series’ serious shortcomings.

I first played Persona 3 and Persona 4 at a critical moment in my life. I was 18, about to graduate high school, and in a few months, I would be moving away from my friends and family to start college in a new city. Those games’ themes of personal growth, finding one’s “true self”, accepting loss, and making the most of what little time you have left with friends, deeply resonated with me. Persona 5 came at an equally opportune time. I was studying abroad in the UK when the game released right in the middle of spring break. Spring break is much longer in the UK than in the US and most of my friends returned home for the holiday, meaning I had little to do outside of traveling and writing my final papers. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Persona 5 filled a void in my life. Even then, back in 2017 with Persona 5, I started to pick up on issues I hadn’t really considered with the previous games.

Sometime later, I convinced my girlfriend to play Persona 5 and, later, Persona 4. We both enjoyed experiencing those games together and in doing so, I was able to revisit those narratives with an older, more critical perspective. With each new re-release of an Atlus game, such as Catherine: Full Body and Persona 5: Royal, there is renewed conversation and criticism around the developer’s handling of LGBTQ+ themes. That conversation inspired me to write about this series and its shortcomings when it comes to representing specific groups of people. Whatever the reason, be it a young, uncritical perspective, willful ignorance, or a general numbness towards anime tropes, I ignored that the Persona series’ problematic history was far deeper than a handful of tasteless attempts at making a joke.

Persona 3 (2006)

In Persona 3 there’s a part where your main characters take a summer vacation to Yakushima. While at the beach, the guys decide to hit on girls, which they dub “Operation Babe Hunt” (..yeah). They fail miserably until they meet one woman who is unusually eager in being randomly hit on by a trio of teenage boys. It’s revealed that she is actually a trans woman when one of the characters notices some hair on her chin, much to everyone’s horror. This scene is meant to be taken as a joke but it plays into the extremely harmful stereotype that trans women are predators, seeking to “trick” straight men into having sex with them. It’s a stereotype that appears in a lot of media and is especially prominent in anime culture, where the slur “trap” came from (it should be noted that the term “trap” is a completely western invention).

Persona 4 (2008)

In Persona 4, LGBTQ+ characters are more than just punchlines for really bad jokes, but there are still shortcomings when it comes to depicting queer themes. Persona 4 is set in a small, rural Japanese town where a string of mysterious kidnappings and murders has taken place. The protagonists come to understand that these murders are connected to the “Midnight Channel”, a strange television program that prophesizes the next murder victim. By literally venturing into the Midnight Channel, a physical manifestation of the victim’s psyche, the protagonists rescue whoever is trapped in the program, preventing them from becoming the next victim. Those rescued promptly join the player character’s team and work to uncover the perpetrator behind the kidnappings and murders.

When in the Midnight Channel, the kidnapped victims are confronted by their “shadow selves”, a concept borrowed from Jungian psychology that is the side to one’s personality that one refuses to acknowledge. It is only through the acceptance of one’s shadow self that we become self-aware and can become our “true selves”. In Persona 4, if you reject your shadow it will attack and kill you, but if you accept it, you gain the power of a Persona and can freely travel in and out of the Midnight Channel.

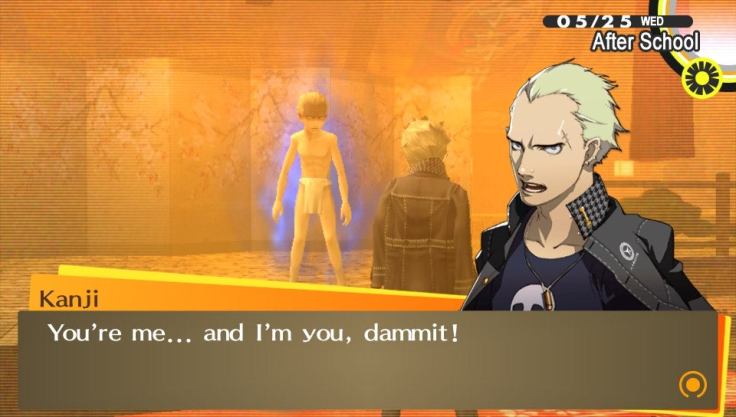

One character in Persona 4 is Kanji Tatsumi, who is introduced as a rough, anti-social delinquent who frequently skips school. When Kanji is kidnapped and trapped in Midnight Channel to become the next murder victim, we discover that his shadow self is actually an effeminate, over-the-top gay man and the Midnight Channel takes on the form of a steamy, homoerotic bathhouse. We come to learn that Kanji is questioning his sexual orientation, which he sees as opposed to his masculine, delinquent exterior. Upon defeating Shadow Kanji, Kanji accepts his shadow self as a part of his personality, but he makes no explicit declaration that he is gay or bisexual. Rather, he says, “It ain’t a matter of guys or chicks…I’m just scared shitless of being rejected.” Following this, Kanji’s character arc focuses on his anxiety over his unmanly interests, such as sewing, cooking, and plushies, and he wrestles with what it truly means to be a “man”.

Persona 4 is very ambiguous on whether or not Kanji is queer and Atlus has left it to players to draw their own conclusions. Shadow selves in the game are not cut and dry; they often exaggerate or twist feelings in an attempt to rile the person up. For example, Yukiko Amagi’s shadow self is a princess that desires a “knight in shining armor” to save her, which later transforms into a bird trapped in a cage. She doesn’t literally think of herself as a princess or wants someone to save her, rather she feels trapped by the expectation that she will inherit her family’s business and wants to have power over the direction of her life.

One interpretation of Kanji’s character is that he is not gay and is instead struggling with the expectations of masculinity in a conservative, highly gendered society. As the son of a widowed mother, Kanji feels like he must become the “man of the house”, and fears that his hobbies make him weird, unmanly, and possibly gay. At the end of his character arc, Kanji realizes he shouldn’t fear what others think of him and he should just be himself, letting others accept him for who he is. He comes to understand that performative masculinity is a mask and that being a “man” is a far more altruistic act.

Another interpretation is that Kanji comes to realize that sexuality and masculinity are distinct aspects of one’s personality. Kanji can be gay, manly, and enjoy traditionally feminine hobbies all at the same time, without being the stereotypical vision of a gay man that his shadow self was. He even says at the end of his character arc, “Now I can say it straight out…that “other me” is me.”

After Kanji joins the protagonist’s party, his internal turmoil over his sexuality and masculinity frequently becomes the focus of another character’s, Yosuke Hanamura, jokes and insecurities. Shortly after joining the main cast of characters, on a school camping trip, Yosuke expresses concern over sharing a tent with Kanji because he is worried about what Kanji might do to him in the middle of the night. Your options for calling Yosuke out for his shitty behavior is unfortunately limited, but the game never vindicates Yosuke’s homophobia and never paints his behavior as something other than petty and immature. It’s important to keep in mind that these characters are teenagers and I’m sure we all knew someone in high school who acted in the same hurtful way as Yosuke.

It’s also interesting to note that there is dubbed English audio that was cut from the end of Yosuke’s character arc where he professes his romantic feelings for the main character, revealing that he was in the closet. I wish this had stayed in because it puts Yosuke’s homophobia towards Kanji and his horniness towards his female friends in a dramatically different light (and explains his obsession over whether or not the player character keeps porn magazines under his futon).

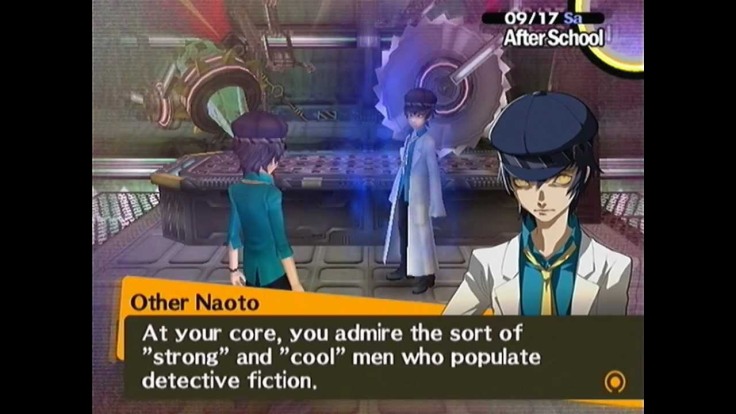

Another character in Persona 4 that touches on LGBTQ+ themes is Naoto Shirogane. Naoto is introduced alongside Kanji as a young detective brought in to help the local police force in investigating the spree of kidnappings and murders. Naoto dresses in men’s clothing, responds to he / him pronouns, and Kanji finds him attractive. Later in the story, Naoto is kidnapped and trapped in the Midnight Channel to become the next murder victim. His shadow depicts himself in an oversized lab coat and speaks of an “experimental procedure” and a “bodily alteration process”. When the main characters confront Naoto and Shadow Naoto in the Midnight Channel, it is revealed that Naoto is actually biologically female. From Naoto’s behavior and the language and imagery used, we are led to believe that Naoto is a trans man.

However, dialogue between Naoto and Shadow Naoto, and Naoto’s acceptance of his shadow reveals that Naoto’s conflict is not rooted in gender dysphoria but rather a feeling of inferiority with his assigned gender and age. As a young woman, Naoto feels like she will never be taken seriously as a detective in a country where the field of criminology is dominated by men. By dressing as a man, speaking in a low voice and putting on a mature disposition, Naoto thinks she will be better accepted by her colleagues. When asked if she does not like being a girl, Naoto says, “my sex doesn’t fit my ideal image of a detective”, and she later cites her interest in murder mysteries and crime novels where the protagonists are hard-boiled, traditionally masculine men.

After accepting her shadow, Naoto continues to dress in men’s clothing but responds to she / her pronouns. Her character arc follows her enlisting the player character’s help in uncovering a series of riddles by the mysterious “Phantom Thief”. At the end of this arc, Naoto comes to realize that she doesn’t need to be a man to be accepted or needed or to live up to her family’s legacy of great detectives. It is her passion for her profession and her unwavering desire to help others that matters most and she accepts that she can be both a great detective and a woman.

Kanji’s and Naoto’s character arcs touch on important social issues, like sexism in the workplace, toxic notions of masculinity and femininity, the need for inclusive role models in fiction, and, ultimately, accepting one’s true self and not trying to be someone you aren’t in an attempt to fit social expectations. The problem, and where Persona 4 really stumbles, is that these characters’ conflicts are introduced to us using queer imagery and themes and then taken in a different direction. It’s queerbaiting, which at best is disappointing and at worst, hurtful. LGBTQ+ characters are rare in video games, especially back in 2008, and it’s even rarer for a game to directly address the feelings and anxieties queer people experience. To have Kanji built up as a gay man realizing his sexual orientation or to have Naoto realize he is trans and then have that discarded is crushing for people who felt like their experiences would finally be represented in a video game.

Taking Kanji’s and Naoto’s arcs in conjunction with the game’s primary theme of seeking the truth, be it discovering the truth behind the murders or finding one’s true self, it can be read that Persona 4 is saying that questioning one’s sexual orientation or assigned gender is not the actual problem, that’s just a symptom of a more socially acceptable issue. It’s pretty damning that all of Persona 4’s characters, not just Kanji and Naoto, find that their true selves are all fairly socially acceptable. No one discovers that their true self is completely outside the mold their conservative, rural community assigned to them.

All this said, I don’t buy the notion that Atlus “chickened out” when it came to representing LGBTQ+ characters. I think Naoto and Kanji were always intended to focus on sexism and masculinity, and the writers and designers misused queer imagery. It’s also worth noting that when we critique these characters, we are applying a western ideal of queer representation to a piece of media that comes from outside a western cultural point of view. In an article entitled “Opinion: Sexuality and Homophobia in Persona 4”, author Samantha Xu writes, “Because outward unorthodox behavior is frowned upon in Japanese society, many people who engage in homosexual activity see it as a world separate from their day-to-day lives. Upholding respectable outward behavior would mean being married, having children and a respectable job, but what one does in their sexual lives is not harshly judged.” She quotes Mark McLelland, a professor of gender and sexuality studies at the University of Wollongong, who states, “…the notion of ‘coming out’ is seen as undesirable by many Japanese gay men and lesbians as it necessarily involves adopting a confrontational stance against mainstream lifestyles and values, which many still wish to endorse.” Xu concludes that Kanji remaining ambiguous about his sexuality is not necessarily a rejection of it or the writers displaying homophobia, but rather a comment on homosexuality in a Japanese social context.

Looking back on the character arcs of Persona 4’s cast, it’s interesting that in seeking their true selves, these characters are often torn between a traditional expectation of them and completely rejecting this expectation, and often end up somewhere in the middle between these two extremes. Maybe this is a message that resonates more with Japanese audiences. Still, this does not invalidate western criticism of Kanji or Naoto nor does it excuse Atlus’s use of queer characters as punchlines. Atlus needs to recognize that their games reach a large audience beyond their domestic market and should be cautious of how their handling of certain identities will read to players around the globe. Furthermore, Atlus has not improved in its depiction of queer characters post-Persona 4, which has retroactively made the game’s handling of Naoto and Kanji worse off.

Catherine (2011)

Catherine is a puzzle-adventure game developed by the same team that produces the Persona series. Described by the studio as a game aimed at more mature audiences, Catherine is about a man named Vincent Brooks, a complacent thirty-something-year-old man who is in a long term relationship with his girlfriend Katherine. One day over lunch, Katherine implies to Vincent that she wants to get married, both because she is ready for this next step in her life and because she thinks marriage will encourage Vincent to grow up.

Later that night, Vincent meets his friends at the local bar, the Stray Sheep, and expresses his hangups on getting married. They also discuss the recent string of unexplained deaths involving young men, all of whom died in their sleep. Vincent decides to stay late at the bar where he is approached by a mysterious, scantily-clad blonde bombshell. He later experiences a terrible dream where he and other men must successfully climb a tower of blocks or fall to their deaths.

Surviving the nightmare, he wakes up in his apartment and, much to his horror, realizes he spent the night with the blonde woman he met at the Stray Sheep, who introduces herself as Catherine. Over the next week, Vincent tries to keep his infidelity a secret from Katherine while also trying to break off his tryst with Catherine, who continues to appear in Vincent’s bed the next morning despite him having no recollection of inviting her, all while dealing with the deadly recurring nightmares and deciding whether or not he wants to be in a committed relationship.

Catherine is a curious game; a cult classic to many. It’s unique in the way it focuses on modern adult relationships and romance, something that is usually relegated to the side, if present at all, in video games. The game’s puzzles (the nightmare sequences) are also sublime and the whole game is wrapped in a stylistic presentation that foreshadowed the style of Persona 5.

Catherine is also a very flawed game. For as much as Catherine dares to tackle sensitive modern subjects and what it gets right in the process, there are plenty of things it gets wrong. The game hinges on the assumption that there is a fundamental difference between men and women, but, psychologically speaking, that really isn’t true and that line of thinking has led to a myriad of misogynistic ideas and practices. That assumption might be worth exploring from a cultural lens, but Catherine lacks the self-awareness and nuance to do so. It is, after all, a game about relationships written by middle-aged men, and I can’t help but wonder how the game would have turned out if women had an equal voice in the creative process. This is especially evident in the way the game handles its two major female characters: Catherine and Katherine. The former is presented as a bubbly, salacious blonde while the latter is depicted as a business-oriented nagging shrew. There are moments where their personalities seem to extend beyond these stereotypes, but, in comparison to the game’s male characters, they are not given enough time to really develop.

This is not to say that Catherine’s male characters are saints, far from it. Vincent is a complacent man-child with crippling indecision and the male friends he surrounds himself with all have fairly unintelligent opinions on women. The one character that serves as a voice of reason and empathy is Erica, a waitress at the Stray Sheep, and a long-time friend of Vincent and his pals. Throughout the game, Vincent and his friends cast vague remarks regarding Erica, and they are uneasy when the newest addition to their friend group, Toby, voices his attraction to her. After Toby and Erica hook-up, Erica appears alongside Vincent and the other men in the nightmare (I’m sure you can see where this is going). It is revealed in one of the game’s many endings that Erica is a trans woman and Vincent and his friends knew her pre-transition. The game then goes out of its way to deadname Erica in the credits.

The way Catherine treats Erica is awful, which is a shame because otherwise, Erica’s characterization is great and she serves as a positive influence in Vincent’s life. Erica appearing in the nightmare sends the nasty message that trans women are actually just men. This reading is complicated, though, when it is revealed that the nightmares were created by the owner of the Stray Sheep, who is actually the ancient Mesopotamian god Dumuzid, consort to the fertility goddess Ishtar. Yep.

Dumuzid created the nightmare as a way of punishing men who would not procreate with their partners, no doubt a commentary on Japan’s declining birth rates. Catherine is actually a succubus sent by Dumuzid to tear men away from their partners in the hope that they’ll find someone else to settle down and have children with. Despite this revelation, I don’t think the game absolves Vincent of any wrongdoing and ultimately, he is still to blame for his plight because of his complacency and indecision. Vincent is cursed by the nightmare because of his apprehension towards commitment and Erica is cursed because she is preventing Toby from finding a partner he can procreate with.

Catherine frames Dumuzid’s perspective and methods as misguided, saying that traditional expectations of relationships are obsolete in modern times, and it makes sense that an ancient fertility god would have a regressive view of gender. Still, with all of this in mind, the game fails to adequately assuage this awful view of trans women when it uses Erica’s identity as a punchline in one of the game’s endings. At Vincent and Katherine’s wedding, Toby bemoans that he wishes his friends had told him Erica was trans before he lost his “V-Card” to her, with Erica teasing, “once that hole is punched, there’s no refund.” This scene once again plays into the hurtful idea that trans women are out to trick cisgendered men into having sex with them.

I haven’t played Catherine: Full Body, a re-release that came out last year. Reportedly, Full Body tries to fix some of the missteps of the original and also has a new character that comes into Vincent’s life, Qatherine or Rin for short (yes I’m serious), who, judging from Full Body’s marketing, is likely a trans woman. Since I have not played Full Body I cannot comment on how the game handles trans representation in 2019 compared to 2011, but judging from the writings of trans and non-binary folks on this rerelease, it seems the game has its heart in the right place but is still rife with transmisogyny. And, in the end, it is these perspectives we should value the most when it comes to this topic.

Persona 5 (2017)

With how Atlus handled LGBTQ+ representation in Persona 4 and Catherine, Persona 5 could have been an opportunity for the studio to correct its problematic history, especially since Persona 5 is thematically framed around the idea of outsider adolescents rebelling against the abuse and corruption of authority. This ended up not being the case and the scant few depictions of queer characters in Persona 5 are in very poor taste.

The biggest example is a scene where the player character and another character named Ryuji are looking for intel on a mafia boss who is extorting their friend. The two are happened upon by a pair of effeminate gay men who proceed to hit on Ryuji, despite him being clearly uncomfortable with the situation. The men then grab Ryuji and drag him away, implying they wish to sexually assault him. This entire bit is meant to be played for laughs and the player character does nothing to help his friend. This scene is outright insulting and uncomfortable, making light of sexual assault and sending the message that gay men are predators seeking to force themselves on young straight men.

This is in a game where the player character, a high school student, cannot engage in queer romances with his peers but is allowed to have sexual relationships with adult women, including a doctor, a journalist, and his homeroom teacher. There is a character named Lala who works at a bar called Crossroads and it’s not entirely clear if Lala identifies as a trans woman, but her character exhibits an overall feeling of warmth and maturity. However, her presence in the game is very limited and in no way excuses the gross representation of gay men in Persona 5.

The game’s fumbling of marginalized characters extends beyond its poor depictions of LGBTQ+ folks, however. One such character is Ann Takamaki, a classmate of the game’s protagonist, whose mixed ethnicity marks her as an outsider. Because of her looks, she is simultaneously ostracized and fetishized by those around her. She has very few friends and is also the object of her gym teacher’s lust, Suguru Kamoshida. This mimics the way American culture fetishizes Asian women, presenting them as “exotic”, “hyper-sexual” objects.

Persona 5’s first arc revolves around the main characters, including Ann, using their power of Persona to dive into Kamoshida’s psyche and make him publicly repent for his history of abuse. This comes to a head when Ann’s friend, Shiho Suzui, attempts suicide and it is implied she was sexually assaulted by Kamoshida after Ann spurned his advances. The way the game handles these heavy and sensitive subjects is done well for the most part in the game’s opening act. It’s after Kamaoshida pays for his abuse that the game’s presentation of Ann becomes rather tone-deaf. A character like Ann should never be defined by the abuse they suffered, but after Kamaoshida, the game has Ann play into a “sexy, ditzy blonde” stereotype.

In the second arc, the other characters convince Ann to pose nude for an art student so they can uncover evidence that his mentor is scamming his pupils. While the male characters do not intend for Ann to actually pose nude, it comes off as incredibly insensitive given the trauma she endured less than a month prior. Throughout the rest of the game, she is treated as the “hot girl” of the party, and never reclaims or controls her sex appeal because Persona 5 is too busy using it to fulfill pandering anime clichés.

Another character that should be addressed is Futaba Sakura, introduced as the protagonist’s caretaker’s adoptive daughter. While it is never explicitly stated, it is clear that Futaba is neurodivergent and her character can be interpreted as being on the autism spectrum. I think Futaba is a really great character, full of intelligence, affection, and happiness, and is a positive depiction of neurodivergent folks.

Her condition is compounded by the trauma she endured as a child when she witnessed her mother’s death and was gaslighted into believing she was responsible. This trauma articulated itself as agoraphobia, depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation. When the main characters first meet Futaba, she is unable to leave her bedroom. By going into her psyche, the party is able to help Futaba realize and accept that she is not to blame for her mother’s death, which helps her overcome her depression and suicidal thoughts (but explicitly does not “fix” her neurodivergent qualities).

The way Persona 5 stumbles in handling Futaba and her neurodiversity is in the way the main characters try to help her after assisting her in her psyche. They want to help Futaba overcome her agoraphobia and social anxiety, and the way they go about trying to “fix” her is by forcing her into various social interactions: talking to strangers, working in her father’s coffee shop, and finally wearing a swimsuit at the beach. The main characters have their hearts in the right place, but it comes off as insensitive considering what Futaba just experienced, and it reinforces the message that neurodivergent people like Futaba need to be comfortable doing what neurotypical people can do so they can fit in.

Persona 5’s core theme of combating social apathy and demagoguery, having the conviction to stand and fight against corrupt authority falls apart when we look at how the game handles marginalized groups, be it LGBTQ+ people, survivors of sexual abuse, or neurodivergent folks. Social solidarity is not solidarity if it does not include those who are underrepresented in society.

I don’t want to downplay the misfit status of many of Persona 5’s characters. I’m sure the player character’s juvie record, Ryuji coming from a single-parent household, and Makoto feeling inadequate in the shadow of her successful older sister, are all pressing issues that carry a heavier social stigma in Japan than in America. Yet, the vision of youth rebellion in Persona 5 is by and large coming from characters who comfortably fit into the status quo. Queer folks are not well represented, Ann’s mixed ethnicity is not really discussed, and there is no depiction of other minority groups in Japan, like Zainichi Koreans, Burakumin, and other immigrant groups. Persona 5 has a narrow view of what resistance looks like and its vision of positive social change leads to a fairly normal, traditionally civil society.

I have yet to play Persona 5: Royal so I cannot speak to what changes, if any, that game made to the original’s shortcomings. The introduction of a new side character, a school therapist, indicates that Royal wishes to handle some of its heavier topics with more sensitivity. In the news leading up to Royal’s release in the west, Atlus localization staff said they wished to change the original’s offensive depiction of gay men. In the new scene with Ryuji, the two men no longer drag Ryuji off to assault him. Instead, they believe that Ryuji is into drag after witnessing him hanging around the Crossroads bar with the player character, and they cart him away to try on women’s clothing. The scene no longer paints homosexual men as predators or uses sexual assault as a punchline, but it’s still a poor portrayal because it sends the message that queer people force straight people into LGBTQ culture. It’s better but only marginally so, and shows that Atlus hasn’t really come to understand the problem with portraying LGBTQ+ people in this fashion.

With all of this in mind, I don’t hate the Persona series. As I said at the start of this article, a few years ago I would have said that Persona 4 was one of my favorite games ever. And, as of the writing of this piece, I still stand by that feeling, even if my admiration for the series has waned over time. It’s okay to like problematic things as long as you can take a critical eye to it, recognize its fumbles and shortcomings, and listen to criticism coming from underrepresented perspectives.

This article is just another stone on the mountain of discourse on the Persona series’ handling of marginalized identities. To this day people are still debating whether or not Kanji is gay. Why? Because as imperfect as Kanji is regarding queer representation, he’s still a great character. There are fans who want to reclaim Naoto as a trans man, canon be damned because he’s / she’s an interesting and loveable character. You see this amount of conversation not just because the Persona series is popular but because they are great JRPGs with an intriguing premise, a large cast of charming characters, and a phenomenal sense of style.

Atlus desperately needs to do better when it comes to representing marginalized folks. With each new release, people are holding Atlus’s feet to the fire over the examples of homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, and marginalization in their games, and this is a great thing to see. If Atlus wishes to continue featuring social commentary in its games, then they need to be more thoughtful in how they depict people of various identities and discard the sexist and queerphobic anime tropes they seem to stuff in all their games. With the Persona series director, Katsura Hashino, and other Persona staff moving to form a new studio within Atlus called Studio Zero and developing a new IP called Project Re Fantasy, I can only hope the new creatives appointed to helm the Persona series will listen to feedback, address its problematic history, and strive to create a more inclusive game with Persona 6. And the Persona studio should go about this by bringing the marginalized people they depict in their games into the creative process, allowing them to share their opinions and experiences.

…

Thanks for reading!

Like this article? Check out more of my content at jacobhamill.blog.

References

Cross, Katherine. “Opinion: Being sexy and not sexist – a look at Bayonetta and objectification.” July 11, 2016. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/276741/Opinion_

Being_sexy_and_not_sexist__a_look_at_Bayonetta_and_objectification.php.

Degraffinried, Natalie. “Catherine: Full Body’s Successes Make Its Reductive Gender Tropes Sting So Much More.” September 05, 2019. https://kotaku.com/catherine-full-body-s-successes-make-its-reductive-gen-1837908259.

Frank, Allegra. “Longtime Persona director hands off series after more than a decade.” May 4, 2017. https://www.polygon.com/2017/5/4/15545254/persona-5-director-leaves-katsura-hashino.

Grant, Carol. “Atlus, We Haven’t Forgotten Your Mishandling of LGBTQ Characters.” December 24, 2017. https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/wjpnam/atlus-we-havent-forgotten-your-Mishandling-of-lgbtq-characters-catherine-full-body.

Higham, Michael. “How Persona 5 Royal Changes Those Homophobic Scenes.” March 31, 2020. https://www.gamespot.com/articles/how-persona-5-royal-changes-those-homophobic-scene/1100-6474849/.

“Japan.” Minority Rights Group International. Last modified April 2018. https://minorityrights.org/country/japan/.

“Men and Women: No Big Difference.” American Psychological Association. October 20, 2005. https://www.apa.org/research/action/difference.

Ro, An. “Stop Pretending ‘Trap’ has Nothing to Do with Trans Women.” October 10, 2018. https://medium.com/@musketmisstress/stop-pretending-trap-has-nothing-to-do-with-trans-women-662622b89fa2.

Tyrfing, Robyn. “Disregard Canon, Acquire Representation: Naoto Shirogane is a Transman.” February 13, 2014. https://gamecola.net/2014/02/disregard-canon-acquire -representation-naoto-shirogane-is-a-transman/.

Wong, Brittany. “Dear White Guys: Your Asian Fetish Is Showing.” May 29, 2019. https://www.huffpost.com/entry/asian-fetish-dating-red-flags_n_5ce6ca27e4b05c15dea89437.

Xu, Samantha. “Opinion: Sexuality and Homophobia in Persona 4.” January 28, 2009. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/112965/Opinion_Sexuality_And_Homophobia_In_Persona_4.php.

Leave a comment